Brooke Struck digs into how evidence-based decision making isn't about finding data to see whether your preferred idea is good or not. Instead, it's about committing to a methodology for gathering evidence and following where it leads, to uncover ideas and refine them over time. He argues that the kind of confidence leaders need today is "the confidence to say 'I don't know'" and structure the leadership approach around that uncertainty.

The conversation explores a tough reality that goes with this: we usually take results personally, as a referendum on our worth. This mindset makes it very difficult to manage so much change, because we need a lot of evidence, and we’re going to get a lot of things wrong on the way to getting them right. We therefore need to be able to discuss them openly and honestly, without letting damage to our ego slow us down (or stop us entirely).

In this VUCA environment, we need faster, more iterative approaches where leaders delegate decisions but maintain clear guardrails about process, strategic intent and values. That calls for strategy and culture to flow together rather than being treated separately.

The discussion lands on a crucial insight for the AI era: instead of trying to forecast the future, organize your entire organization around change itself—build capabilities for uncertainty rather than trying to control outcomes that we never could.

- On new definitions of confidence

“The type of confidence that is called for is the confidence to say 'I don't know'—the confidence to not only acknowledge ignorance, but embrace it and actually structure our leadership around what we don’t know.” - On how to grow from setbacks and not to take them personally

"Your outcomes are a reflection of your process, not of you as a person. Therefore, when there are failures, this is not a personal attack."

- On leaders starting change with themselves

“The real question to ask is seldom 'How can I convince people to behave differently?' It's more 'What am I doing already that is convincing people to behave in the way that they're behaving now?”

- And the importance of leading change through action

“Culture change cannot be just a communications plan. It can't be those four or five words that you print in huge font on your walls. If that is the extent of your culture work, your cultural interventions, you will have very little impact on the organisation that you're leading.” - Smart investments in times of change

“How do we upskill people if we don't know where things are going? Help them to build skills to figure out how to adapt to change.”

Part 1: Opening & Introduction (00:00:00 - 00:11:05)

Angela Shurina: Brooke, thank you for joining me on Change Wired podcast, the show where we talk about all shades and sides of change, leadership, change management, personal and collective transformation. We grow, unlock more of our potential and create a better world. Thank you for joining the show.

Brooke Struck: Thank you for having me. It's a pleasure.

Angela Shurina: It's amazing to connect with you. I've been following your work in one way or another for quite some time. Right now it's The Decision Lab, and then I found Behavioural Corner Podcast, or Decision Corner.

Brooke Struck: Decision Corner.

Angela Shurina: Decision Corner, yes. I listened to a lot of the episodes, so I feel like I'm listening to the voice that I've listened to for hours already. It's cool to connect here.

Brooke, I always ask my guests to do a little bit of self-introduction—what you'd like our listeners to know about you and your work before we jump into our conversation so they have the right kind of context.

Brooke Struck: Sure. Thank you for having me on. Thank you for giving me a little bit of space to share some ideas. It's always a pleasure to exchange with you and to share those insights with audiences.

A bit of background about me: I got very interested in organisational decision making about 10 years ago now, maybe a little bit more. Very interested in evidence-based policy and evidence-based decision making. Probably 3 or 4 years into that journey, I realised that thinking about organisations as decision makers was useful in some ways, but I also needed to be thinking about people making decisions in organisational contexts. That's really what brought me into behavioural science, decision science, and ultimately to The Decision Lab and to becoming the host of the Decision Corner podcast.

Fast forward a couple of years, The Decision Lab had grown already and was continuing to grow. What I saw was that I really wanted to come back to those roots of organisational decision making, especially in the context of leadership. I wanted to get into conversations around strategy and around organisational culture to improve the decisions of people inside of organisations rather than primarily working on decisions of citizens or consumers or stakeholders—the people that organisations affect externally.

That was about the time that I founded Converge, which I've been running for about 3 years now. That's really focused on strategy development, organisational culture development. To your point earlier, there's a personal growth, leadership development aspect to that as well that's really come to the fore in the work that I've been doing in the last few years. It wasn't something that I was expecting initially, but it's really become a prominent feature of what I'm working on now.

Angela Shurina: I think at the end of the day it's all about people making decisions, growing, changing their behaviour. I read somewhere that if you can't understand change on a small scale of an individual, you can't really understand change at the bigger scale. At the end, we as collectives consist of individuals who are influenced by circumstances, environments, and histories and whatnot.

You mentioned many things that I want to sort of open up a little bit. I think the first thing you mentioned was evidence-based. Can you explain to our listeners what is evidence-based and maybe what it's compared to and how it is different?

Brooke Struck: Evidence is a thorny thing. My PhD is in the philosophy of science, so I have a lot of things to say about evidence. What I'll say now is maybe just a caveat—only a few of those things that I'll say about evidence are at all interesting to people who are not philosophers.

I'll put a bit of a bracket around that and say when we talk about evidence-based, usually what we're talking about is information data, which can be quantitative or qualitative, that's gathered using a defined and consistent methodology. Often that will be contrasted to intuitions or values. There's a very superficial level at which people say evidence and knowledge on the one hand is juxtaposed against superstition and bad ideas on the other hand, which I don't think is all that helpful.

I also don't think that it's helpful to draw a hard division between facts and values, because values go into methodological choices about how we gather evidence. Even the choice of which evidence we gather versus which evidence we don't gather—that is a values-laden decision. A lot of people might want to push back against that saying if values are involved in evidence collection, then you're losing objectivity.

Again, there's a lot of potentially not all that interesting stuff that I can say about that, but there are some people who really like to go down that rabbit hole and I can enjoy following them. Maybe this podcast is not the space for that.

The distinction that I want to draw instead is more about how we engage in conversations about evidence. When we think about the decisions of which evidence to gather and which not to, who gets to participate in those decisions? Who gets to participate in those conversations? That I think is a very important point.

When we are looking at the evidence that we've gathered and trying to interpret that evidence and figure out what it's trying to tell us, who gets to participate in that conversation? This conversation around meaning making—that's really important. It's important from an inclusion perspective. I don't just mean this superficial diversity, equity, and inclusion—it's just the right thing to do. I think those narratives are not that helpful.

There's a real point here around making collective decisions and committing to those collective decisions. If people feel that their voices aren't heard in a conversation, they are much less likely to commit to the outcomes of those conversations. Here we see the behavioural tie-back right away. If people are involved, if people feel that they have contributed to a conversation, that their voice has been heard, that their perspectives have been integrated, they feel a sense of ownership over the outcome of that conversation. Therefore they will have a higher degree of commitment to the outcome of that conversation.

That's something that I bring even into the evidence gathering and evidence interpretation conversation. We need to involve those people that we want committed to the outcome in the process of reaching that outcome.

Part 2: Evidence-Based Decision Making & Uncertainty (00:11:05 - 00:25:00)

Angela Shurina: Also, what it makes me think is when we talk about evidence-based, it feels like it's more about a predetermined sequence and process of decision making versus what's not evidence-based. It's more like, "Okay, we're doing this, but it feels like we should pivot." When you ask people to explain how they made that decision, they don't really have a clear answer like how they came to that conclusion. For me, that's kind of the main difference.

Brooke Struck: Evidence is an interesting thing in this. A lot of people will say, "Well, we should pivot because of this data point." Unless you peel back the layers and look at how that decision was made, that can look like a very rational decision-making process on the surface. "Oh, this person is making a decision based on a data point."

The challenge is that there's much evidence out there. There's much data out there. Once you have reached a conclusion, it is not difficult to go and find data that supports the conclusion that you want to.

Angela Shurina: The confirmation bias.

Brooke Struck: Exactly. This is not something that's done intentionally. It's not malevolent. It's not bad-spirited or anything like this. It's just our cognitive hard-wiring to go and seek information that reinforces our existing beliefs. We can do it completely with the best of intentions—that we go out and find more and more evidence that supports the perspective that we already hold.

The thing for me that makes evidence-based really powerful is to align as a group through the process, not on "this is the outcome that we think is the best and now we're going to go and collect evidence." Rather, "this is the approach to evidence collection that we think is going to give us the most robust answer, and we pre-commit ourselves to say now we're going to go out and collect that evidence and we are going to follow what that evidence tells us."

That commitment to methodology rather than outcome is a really important distinction.

Angela Shurina: That's exactly what I understand about evidence-based—committing to the methodology, to the process and being not attached to the outcome at all. It's like in scientific method, you're wrong until you prove the opposite. The whole point is to not commit to any outcome and then try to prove it, but instead have a methodology and then see what comes out of it.

Brooke Struck: That has a huge personal growth aspect to it as well. It is uncomfortable to do that. It feels very counterintuitive. It feels very exposing. It feels full of risk, all of which is true. Yet we will still reach better decisions and we will achieve stronger commitments to those decisions as a group if we follow this process as opposed to following a different one.

Angela Shurina: Do you think in our today's world where change is accelerated and I guess there is a lot more data and it also changes at a faster pace—do you think evidence-based still holds the same power when it seems like data points and what we collect changes just every time we collect it?

Brooke Struck: I absolutely think that working in an evidence-based manner continues to be relevant, continues to be important, perhaps more than ever. What needs to be calibrated is our patience, our appetite for risk. We might need to be comfortable—and maybe I'll make a stronger statement—as things continue to move faster around us, we need to become more and more comfortable making decisions on less evidence than we might want.

We will not feel as reassured. The evidence will not be as conclusive as we might want it to be. We might not feel as comfortable with the decision at the moment when we say, "Well, we have to jump now or not." Whatever choice we're going to make, leap or don't leap, we will probably have to make that on the basis of less evidence than we would want, with a feeling of greater discomfort than we might prefer.

Angela Shurina: That actually brings me to a very important point that you mentioned in one of your articles or podcasts around—now that we have less data and we need to act with less certainty, if you are a leader in charge of hundreds, sometimes thousands of people, how are you supposed to look confident and share this confidence or show this confidence to people and then ask them to leap and to act when you actually don't know how it's going to turn out?

Brooke Struck: I would challenge the idea that we need to show confidence, or that the way that we typically think about showing confidence is the right way to lead right now. I think that right now the type of confidence that is called for is the confidence to say "I don't know"—the confidence to not only acknowledge ignorance, but embrace it and actually structure our leadership around that ignorance.

To say, "Okay, I want you to be making these leaps as the team around me. I need you to be making these leaps. We need to make that safe both for the organization and for the individuals." For that reason, we set up very specific guardrails about how large a leap can be at first, until it demonstrates a certain level of credibility, at which point we invest a little bit further and delegate those decisions.

We know that there are just more choices that need to be made inside of this organisation than can be centralised and made in the C-suite. Therefore, these are the range of decisions that we are delegating. Here's guidance about how we would like you to make those decisions, and we are going to support you in making those decisions.

We're making it clear that we're not rewarding on the basis of outcomes—we're rewarding on the basis of process. Sometimes the best decision possible still turns out badly. The flip side is also true: sometimes bad decisions still turn out well.

Making sure that we are really being thorough about the process—when something doesn't work, what we want to look at is how good was the decision-making process? Did you make the best decision available to you at the time? The same thing is true of success.

This is something that I believe the US Marines are very explicit about. They do an after-action review as soon as a mission is complete—they do a review immediately whether the mission was a failure or a success. That is really key here. They're hyper-focused on process. What were the decisions that were made? How were those decisions made? How might we improve the decision-making process moving forward, even in situations where everything turned out exactly the way that we'd hoped, or pretty close?

Part 3: Confidence, Personal Growth & Systems Thinking (00:25:00 - 00:44:00)

Angela Shurina: You mentioned this insight that I think I first read in the book by Annie Duke, either "Thinking in Bets" or something around decision making. It was profound for me to understand that even a good outcome might be a result of bad thinking or bad decision making. It's true the other way around as well. A bad outcome might be the result of good decision making.

We really need to understand the process of decision making itself, not judge just the results. It's kind of like there is this personal bias—if I succeeded, I don't need to look into that. It's all good, let me just move forward. When you fail, you stop and start thinking again, "Where did it go wrong?" Whereas if you did succeed, you also need to analyze how did you end up having that success.

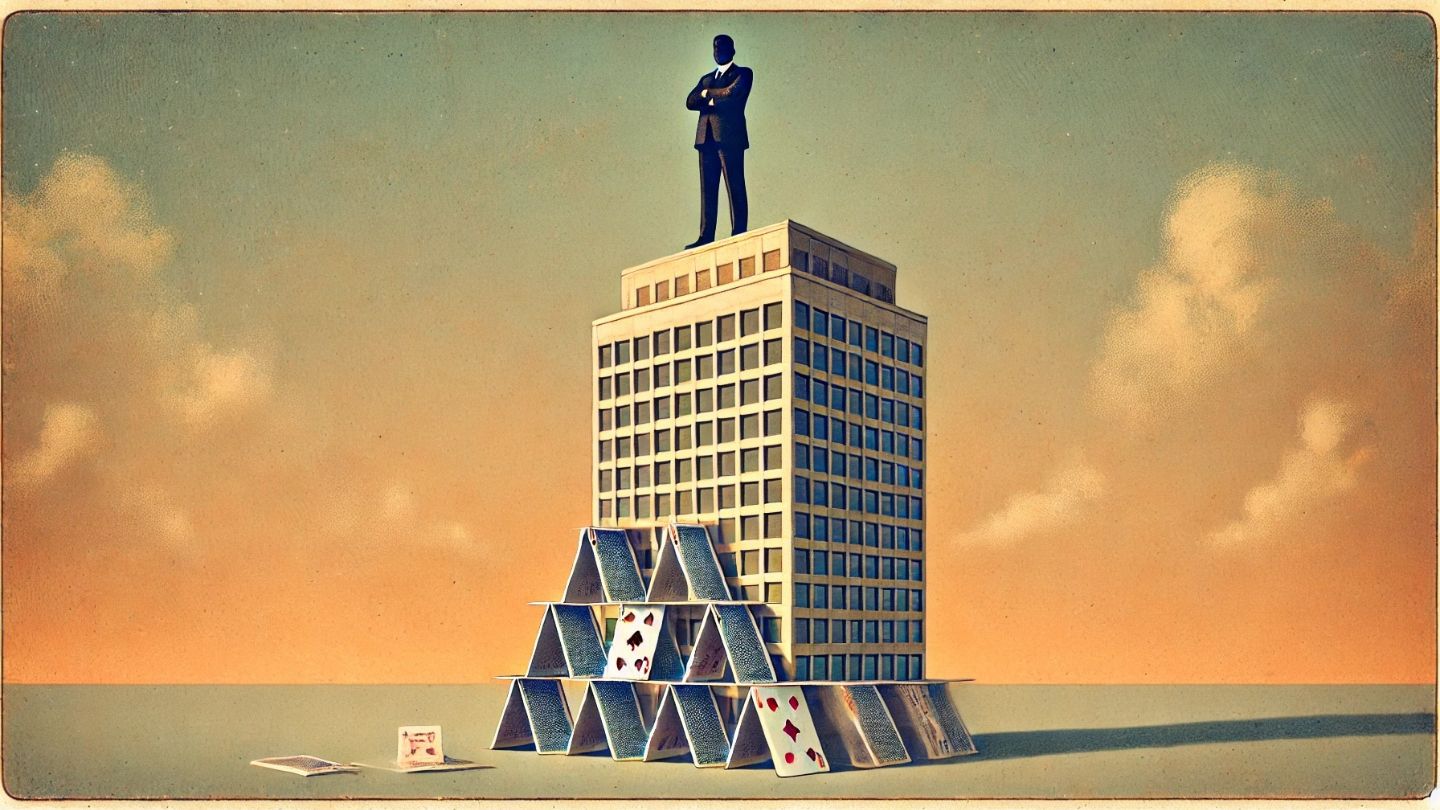

Brooke Struck: I want to loop back to confidence in that context and personal growth that comes with that. How can we be confident in the face of many decisions that turn out poorly? Let's think about venture capital, for instance. Part of the model is they want to be taking bets on such big gambles that they know that the vast majority of them should fail. If the failure rate is too low, that's actually an indicator that they're not taking enough risk in their portfolio.

How do we maintain confidence in the face of much failure? I think the solution to that is to really revisit what confidence means in this context. It's the confidence to say even though a situation turned out poorly, this is information. This is feedback. This is evidence for me to think about how it is that I'm working.

That takes an enormous amount of personal growth to take ego out of the equation. Your outcomes are a reflection of your process, not of you as a person. Therefore, on the one hand, when there are failures, this is not a personal attack. A product launch failing is not a reflection of your value as a person. Similarly, when something goes well, this is also not a reflection of your value as a person.

Recognizing that actually the feedback that the market is giving us about different offerings is not about us. It's not a reflection on our value as individuals. That sense of confidence, that ability to step back from that feedback and say, "I'm confident in my worth and in my value as a leader, as a contributor, as a person, as a family member, whatever that is."

I'm confident enough in my value that I can look at this feedback. I can look at this information that I'm getting from the world around me and not be destabilized by that. I'm confident enough to go and stare a hard truth in the face, and I'm confident enough to set up an organisation that does the same thing—that stares into the hard truth and doesn't blink and doesn't flinch.

I'm willing to support the people around me in doing that as well, even when the results that they get are not the results that I hope for. But if they're following the right process and if they are learning, I have confidence that in the long term, the things that need to happen will happen. The results that we're looking for will come about, and I'm not destabilized by it in the short term. That to me is a very strong position of confidence for leadership that's well calibrated to the 21st century.

Angela Shurina: While you were speaking about that, I thought that this process has to be communicated and somehow transferred throughout the whole organisation. What I found in my work also is that leaders sometimes assume that everyone thinks this way because "I once said it somewhere, therefore we all got it." But repetition is the mother of all skill, and it needs to be present in order for anything to sink in. Plus, there are new people coming, people leaving, and it has to be repeated in many ways and many times so it becomes part of culture and not just part of a few leaders' mindset at the top.

Brooke Struck: I would build on that. First of all, yes, I totally agree—you need to say something, or rather you need to hear something a thousand times before you really hear it for the first time. That's part of it. Your strongest communications are your actions.

Really demonstrating through your own behaviour how it is that you are acting in this way, not just sending out nice communications, but also being transparent about the process that you yourself are following and modelling the behaviour that you hope to see from others. Beyond this as well, embedding it into processes, embedding it into systems. The way that we work, the structures that we set up to guide the actions that we take in our day-to-day work are powerful in setting that organisational culture and in establishing that mindset that's shared around the organisation.

Culture change cannot be just a communications plan. It can't be those four or five words that you print in huge font on your walls. If that is the extent of your culture work, your cultural interventions, you will have very little impact on the organisation that you're leading.

This for me is why it's important to have culture tightly integrated with strategy and to have—from a role division perspective—something that I'm seeing more and more is that the organisations that are strongest on culture and really nailing it with strategy and being able to implement strategies and cascade those strategies effectively throughout their organisations. More and more, I'm seeing that those are organisations where there's a strong relationship between the CEO and the chief people officer or the chief HR officer.

When that happens, we get past culture as communications. Culture is not just something that is managed inside of the HR function. Culture is more strongly determined by our actions than any words that we might say. The actions that an organisation takes are cutting across all functions. We need to think about operations. We need to think about marketing and sales. We need to think about every function inside of the organisation as a lever that influences culture.

This is where that tight relationship between the head of HR and the CEO is very important, because if the CEO takes the perspectives of the culture leader seriously, there will be opportunities for those cultural interventions to really cascade across the functions of the organisation. If HR is in its box and needs to stay in its lane and doesn't have serious attention from the other executives, almost by its nature we know that cultural interventions are going to have a very weak effect.

Angela Shurina: Culture—I read it somewhere—culture is not what we say, but what we repeatedly do. Words are always easier than to take action. Also what you made me think about when we want to promote certain behaviour, it's not just example. It's also to a huge degree what we incentivize, what we praise people for, what we make public and draw everyone's attention to, what's the easiest.

That goes actually to behavioural change and design for behavioural change. I always use this phrase: cultivate workplaces where human potential growth would flourish. For me, it's always been true that when you create the space for certain things and behaviours to flourish, that's what's going to happen. When I say what you communicate, what I mean by communication—yes, it's not just words. It's also actions. It's also example. It's also what bonuses are given for. It's also what is praised, and what's made easier.

Brooke Struck: We don't rise to the level of our goals. We fall to the level of our systems.

Angela Shurina: That's going to feel like the bridge. I always think of your work—I think of design for behavioural change, but I also think of decision making. I feel like they are very interlinked. The decisions we make influence our behaviours directly, and those decisions are shaped by everything around us. And that's where also...

Brooke Struck: The leadership and culture piece and the strategy piece are an important part of that as well. The reason that I really focus on that space is that the decisions that are made at those leadership tables, once they are cascaded through all the systems of the organisation, are an enormously powerful lever for change.

If we think about, for instance, the massive explosion of interest in behavioural science during the COVID pandemic. One of the things that I saw in that is that the heightened attractiveness of behavioural science and decision science at that time was in large part driven by the idea that we didn't need to change policies. We didn't need to change regulations. We didn't need to change legislation in order to change behaviour. It was like, "We get to change behaviour. We get to have more of the outcomes that we want without doing the hard work of actually changing regulations, policies, these kinds of things."

I think that is really problematic. The idea that we just relinquish and abandon this conversation about good leadership in order to move to the right behaviours. I think that the leadership conversation is one that we need to not abandon. We need leadership conversations now more than we have needed them in a very long time. I think we're in a bit of a crisis of leadership. We don't see a lot of good leadership around us right now.

I'm really flipping the thing on its head and saying, yes, all these tools of behavioural science and decision science—they're extremely powerful and we should use them. The place where we should start is with ourselves, especially as leaders.

Part 4: Behavioural Science & Leadership Integration (00:44:00 - 01:02:00)

Angela Shurina: Can you expand on this a little bit more? What do you mean? How do we marry behavioural science and leadership? Where do you see leaders maybe lack or need to incorporate those? What would be maybe an example, maybe through specific behaviour—good leadership married with behavioural science?

Brooke Struck: If I think about this in a policy context, a lot of conversations in behavioural science in a policy context are focused on how we can get citizens to access a program more. How can we get them to take advantage of a benefits program more than they currently are?

This often gets reduced to communications. We think about communication, or we think about behavioural science and that whole toolkit as a communications toolkit. "We will be able to better communicate the value of the program in a more timely way, etc., to improve uptake and adherence to program X."

That's, I would say, the thin interpretation of how behavioural science can help us to improve policy. One step deeper than that is to say, "Okay, well, behavioural science actually can tell us a lot about why people are not adhering to this program. It might not just be that you haven't communicated benefits clearly or in a timely way, or that you don't have very polished and smooth UX. The problem might be that actually the program is not very well designed for the people that it's supposed to be helping the most."

The next layer there is to say, "Okay, we're going to use behavioural science for messaging, and we're going to use it for program design. We're not just going to message a program differently. We're going to design a program differently." That is already a much bigger task than just changing communications. The number of people inside of an agency or department who need to sign off on communications changes is relatively small compared to the number of people who need to sign off on a change in program design itself.

That's kind of a second layer. A third layer, then, is to say, "Okay, well, how is it that we are making decisions internally about how to structure these programs? How is it that we arrived in a situation where the messaging around the program is not as effective as we'd want it to be, and actually the program design is not as effective as we want it to be?"

Oh, it turns out that those were the very predictable outcomes of the decision-making processes that we've set up inside of our organisation. If we continue to make decisions about communications, decisions about program design in the way that we've been making them, we should expect that we will continue to get the kinds of outcomes that we're getting now.

That's the third layer. Then the fourth layer is at the leadership level. How is it that I'm leading inside of this organisation that makes these kinds of decision-making processes the most likely ones to come up? Why is it that the way that I talk about and the way that I demonstrate my relation to uncertainty, my relation to risk and fear and these kind of things—how is it that I, as a leader, showing up day after day, behaving in these ways, is creating an organisation where nobody can talk about risk openly? Nobody can really undertake effective experiments because everything needs to be a success. Nothing is allowed to fail, and therefore we have no space in which to learn.

What is it that I'm doing as a leader, showing up day after day, that's creating that kind of circumstance? Because that ultimately flows all the way down the cascade. If I change my leadership behaviours, that will change the kind of culture and the kinds of systems and processes that we have inside of our organisation, which will change the kinds of programs that we design, the kinds of communications that we design in order to convey the right message to the right people at the right time, etc., which ultimately leads to the kinds of behaviours and outcomes that we're looking to generate through our policy.

Angela Shurina: It reminds me of this phrase: every system is designed to—is perfectly optimized to get the result it's getting.

Brooke Struck: Absolutely. I'm a hundred percent on board. Systems thinking is a big part of how I think about and try to interact with the world. I think about what it is that makes outcomes consistent.

I remember I went to a talk about six months ago, and it was a very respected economist who was giving this presentation about how certain geopolitical dynamics were expected to change and macroeconomic changes that were coming from that. I asked specifically—this was in a Canadian context; I'm based in Canada for any listeners who don't know—thinking about the productivity gap.

For decades and decades and decades, productivity per employee in Canada has been chronically lower than productivity for analogous workers in the United States, in European countries, etc. I asked, "Well, what about that productivity gap that's just been this glaring problem for decades? What is driving that and how do we expect that to change?"

The economist's answer was, "Well, there's nothing really driving that." I pushed back, and to your point around a system is optimized to produce the outcomes that it generates consistently—if things don't have a reason, they're random, they fluctuate like crazy. If we see a consistent, stable outcome, it's because there is a reason underneath that that is driving that consistency.

We got into a conversation about what it is about the history of Canadian economy—it was a very interesting conversation—that has produced this productivity gap. But that broader point is a very strong one. If there is an outcome that you're seeing that you consistently don't like, it's because of some feature of the system design that you are seeing that consistency.

The real question to ask, for me anyway, is seldom "How can I convince people to behave differently?" It's more "What am I doing already that is convincing people to behave in the way that they're behaving now?" Because that's the thing that I will need to change. Often the power of that completely blows out of the water what we will do with just a communications shift.

Angela Shurina: Again, such a powerful concept. It's powerful for changing organisations and collectives and governments, and also for personal change. Everyone's life is optimised for the result that the person is getting. If you want something different, well, you better look at what your life is optimised for and how to change those different factors so you get the different result. That's why just changing location would often produce different results even if you change nothing else.

Brooke Struck: There are two questions that I find really powerful in that respect for leaders. One is: why is the continuation of the status quo not acceptable? Why is the same result 12 months from now, 24 months from now, not totally fine and totally adequate? Because if there isn't discomfort with those results, there will not be sufficient motivation for change. That's one.

The second question is: what are the ways in which I am benefiting from and complicit in the outcome that I say that I don't want? Because often there is also a benefit that comes from that.

If we think about, for instance, "Oh, I want more innovation inside of my organisation. I want people taking more risk." But I myself, as a leader, I don't take any risk. When I have failures or I have experiments that don't turn out the way that I had hoped that they would turn out, I don't share those things. I only share success stories. How is it that I'm benefiting from that? Well, it's allowing me to shield my ego.

Coming to terms with the fact that there are real benefits that each of us is getting from the circumstances that we're participating in that we say that we don't like. I talked about this question earlier of why is continuation of the status quo not acceptable? That's to drive the motivation for change.

The reason the second question around how I'm benefiting from the status quo is important is basically—not to put it in grand terms—that comfort that you're enjoying, that benefit that you're enjoying from the status quo, that's the thing that you're going to put up on the altar and sacrifice in the name of change.

Angela Shurina: It's like we all want innovation, but we all want innovation if we are winning in it. We don't actually want it when it gets messy. But before we actually get to a new sort of equilibrium or new status quo, there has to be mess, and it's going to be uncomfortable. We often don't want this and get frustrated and upset.

Also to the second point about status quo—we humans are creatures of habit, and we don't like to be changing actually at the core when there is no reason. That's why they say in change management, you've got to first communicate the urgency and the reason. Otherwise nobody would want to change their behaviour, would just try to keep things as they are as long as we can.

Brooke Struck: To my point earlier, this is where collective leadership for me is such a powerful intervention. Yes, it's very well-received wisdom in the change management world that you need to communicate urgency. Putting my behavioural hat on, I want to step that up one further.

It's not just about communicating urgency. It's about giving people the opportunity to define that urgency. One of the challenges with communicating urgency to people who have not participated in a process of defining it is that what's urgent to you might not be urgent to them.

You might say, "Oh, well, it's super important that this change because in 18 months this is going to happen." If they don't care about this that's happening in 18 months, they will not be motivated to change. Having them participate in that process of co-defining what that urgent situation is makes them much more motivated to actually implement the changes that are needed because it's their change. It's not your change that is being imposed on them.

Angela Shurina: It's like there is a source of wisdom in change management. I think it was popularised by "What's in it for me?" What's in it for me is different than what it is for the leader of organisation. I often would talk to people who, for some reason, are about to retire, and they don't want change. They don't want to talk about change. They just want to retire. For them, there is literally nothing. They're not the right people to talk about change.'t want change. They don't want to talk about change. They just want to retire. For them, there is literally nothing. They're not the right people to talk about change.

You're right. We are humans. We like to contribute, but we also are very selfish, and we need to never forget about that.

Part 5: AI and Strategic Transformation (01:02:00 - 01:20:00)

Angela Shurina: Speaking of change management, I also definitely wanted to touch upon a lot of change management that is happening right now due to AI and all the transformation that is just happening in an ongoing fashion. I always hear from leaders, "Well, we roll out one thing and it gets outdated. Should we do something? Should we just do nothing and wait for it?"

Also strategy—does it make sense to do any strategy? What's your take on that from the perspective of decision making and behavioural science? What should leaders do in this situation?

Brooke Struck: Yes, I think that strategy is still relevant. I think that strategy as a process needs to accelerate. Our strategy processes have been calibrated to a certain pace of decision making. As that pace of decision making has increased because of the increased pace of change around us, the strategy process needs to rise to the challenge. It needs to meet the moment.

Thinking about strategy not as an exercise that you do annually or that you do every three years—that is like this massive effort and undertaking where your entire leadership team is basically out of commission for huge chunks of time. That, I think, is an ineffective way to be doing strategy moving forward.

I think strategy needs to be smaller, faster, and more iterative. This is where we start to see a big connection between strategy and culture, where actually we are creating organisations that have a culture of thinking and acting strategically.

This is—I was talking a bit earlier in our conversation about the delegation of decision making. How is it that we can delegate that decision making effectively? I talked about giving clarity about the process of how you want decisions to be made and where the guardrails are and how performance is going to be assessed around that.

There's also a big piece of substantive context. This is the differentiated position. This is the competitive advantage that we want to be nurturing. In making your decisions in these ways, we want you to be leaning into serving customers that look like this rather than segments over here, because those segments are ones where we don't feel that we can develop a sustainable competitive advantage.

We're developing these kinds of core capabilities, these differentiating capabilities inside of our organisation because we feel that those are the ones that are going to position us to win with this segment of clientele that we've selected, where we don't feel that competitors or other alternatives will really be able to dislodge us as the best choice for that clientele that we've selected.

Really making that clear across the organisation to guide the substantive direction of conversations. Again, to the point we were making earlier about uncertainty, about innovation, also clearly indicating: these are the elements of our strategy about which we have high certainty or high confidence, and these are the ones where we know that our strategy is full of assumptions. It's full of hypotheses.

It's very important for you, across the organisation, to be escalating the signals that you're seeing from the marketplace, from our clientele, from our partners, from our funders—whoever those various stakeholder groups are. We have made bets about how to position ourselves strategically that rely on X and Y and Z being true, and we don't know if they are.

Part of what we need to do is actually build the evidence base that our strategic position is the right one for us to stake out. We need to know what it is that you're seeing, because it's always the frontline employees who have that most direct access to what signals the market is giving them, be that customers, be that partners or other stakeholders.

How can we create an organisational system and, along with it, the culture to make sure that those signals get escalated effectively so that we can meaningfully reflect on what it is that the world around us is telling us? Again, to that point of feedback and information and taking ego out of the equation—what is it that the world around us is trying to tell us about what we are trying to do?

Which parts of it do they like? Which parts of it do they not like? Are there client segments that are resonating really strongly with this that we had disqualified or that we had not considered that actually are showing real promise as places for us to go and play in the market where we think that we can have a sustainable competitive advantage?

Those kinds of insights are really the aggregate of a bunch of tiny signals that are being collected throughout the organisation. To come back to this question about strategy—strategy making is one that needs to be done on a much more continuous basis where we are reflecting on those signals, where we're actively paying attention to what the world around us is trying to say to us so that we can make informed decisions about which direction to take.

Angela Shurina: Also, there has to be a clear system for gathering that data, for gathering that feedback, for escalating it, for then making decisions. It's not something that you believe people should just get, but there has to be again an easier, very well-communicated system. It has to be reinforced in order for people to actually do it. Then you have to obviously measure whether it is actually happening—this feedback loop, this information gathering or not. If not, then what can we do about that?

Also, throughout your conversation, and again somewhere in your articles, you mentioned this—that leaders need to learn how to switch from this mode of trying to control to then encourage and educate about good decision-making process, which then can and will lead towards the outcome that we seek in terms of whether that's feedback, decision making, or certain practices and innovation running in a certain way.

I want to ask you a question that I also am often asked and I'm not sure I have the answer. I wanted to ask you that as well. With all the AI happening, leaders feel like, yes, they need to delegate more and they need to give more decision-making power. But they're not sure that junior members of the team can make those decisions because they don't have that vast experience that leaders usually accumulate as they move up the ladder. They're wondering, "How can we delegate if we're not sure if they're capable of quality decisions?" What's your take on that? How maybe leaders can work around that?

Brooke Struck: There are a couple of things there. The first is that as people gain more context and as they gain more practice, they will get better at it. The second is that this is not a binary situation. This is not like a dial that has two settings—zero or one, delegating or not delegating.

Really thinking about how we can take the next step towards more delegated, more decentralized decision making and thinking about the leader's own level of comfort there as well. If where I want to be 15 steps from now is at this place where decisions that look like this, that, and the other are all decentralized and these kinds of things—what is the next step that I, as a leader, am ready to take right now?

What's the step along the path that feels uncomfortable but just safe enough for me to take? What is it that I need out of people making those decisions? That's a very personal, introspective question that's incredibly important in order to define an effective path for decentralising decision making.

Which decisions am I comfortable letting go of? What would I need to know is the case about those decisions in order to feel confidence that they're being taken properly? That thread, pulling on that, will help to identify which decisions to delegate and what kinds of systems and processes to put in place to ensure that the people to whom those decisions are delegated are positioned to succeed and that the leader also has the visibility that they need even as they relinquish control.

Angela Shurina: I also think, building on that, you can just also talk to people—meaning ask them, "You need to make this decision. What information, what support do you need to be able to be comfortable making these decisions?" and then provide those resources.

Brooke Struck: Right. I talked about that from the leader perspective—what does the leader need in order to be positioned to succeed and to feel comfortable and confident in these kinds of things? But you're absolutely right. Exactly the same thing is true as a mirror image with the people to whom those decisions are being delegated. What is it that they would need in order to be in a position to succeed? What is it that they would need in order to feel comfortable and confident?

Often we talk about centralisation of decision making as though this is something that is, in a certain sense, unilaterally imposed by leaders, and all of the people below wish that they had more decision-making authority. They're just waiting to be unleashed to make more decisions. No, no. There is a lot of ego risk and professional risk that's bound up for those employees as well.

The system is in such a stable equilibrium state, not only because the leadership is benefiting from and enjoying the setup, but also because the people reporting to that leader are enjoying it as well. It's like if there's peace everywhere on the terrain, it's because everyone is happy with the setup.

If people were unhappy, if actually they were ready to take on more decisions and they didn't have any reservations about taking on those decisions, you'd have a lot of grumbling and potentially active warfare here and there.

Angela Shurina: Again, people love status quo. People love predictable things. People love things as they are on all levels in all directions. It's not just leadership or frontline employees. It goes both ways. Also, I guess what I wanted to mention here is we all have different comfort zones with change and innovation or things being uncertain. There are always—I found it's beneficial when we find those people who are more comfortable, who are less comfortable with that, so we could also communicate in a certain way or delegate decision making accordingly to that.

Brooke Struck: I think a lot of people wish that they had more authority, but they're also very comfortable having a lower level of accountability. If you offer them both, they might not necessarily take you up on it.

You might say, for example, "These decisions are now under your control," and then find that you've got a bunch of team members who then come to the leader anyway and say, "This is what I'm thinking about. Basically, how would you make this decision?"

In their behaviour, they're doing exactly, basically exactly the same thing. They are looking to make sure that the accountability resides with their leader even though they've been given the authority. At the end of the day, the actual decision-making process doesn't change that much.

This is where asking that question about "Well, what do you need to succeed? What is it that you need to feel confident and to feel safe in making these decisions?" That's an important question, because otherwise you're very likely to have people running back to exactly the same kind of accountability sinks that they were seeking before.

They don't want to be the ones to wear a bad outcome. If you don't give them clarity about how outcomes will be assessed and these kinds of things, in their behaviour they will probably revert to something very similar to the situation that you're in now. Whereas if you want substantial change, there's more that needs to happen in terms of system redesign as opposed to just delegating authorities to different people.

Part 6: Innovation and Scenario Planning (01:20:00 - 01:38:00)

Angela Shurina: I remember this reminds me of a couple of talks I gave at Innovation Day in companies. Innovation people—actually my favourite people. I would come to those talks and the leader would tell me, "Well, here is your space," and I'm like, "What do I do here, do you think?"

Brooke Struck: Innovate.

Angela Shurina: Exactly. But I think when you work—I don't know what's your experience, but my experience when you work with well set up people who are a good match for innovation department, they're those kind of people. They are okay with being given responsibility, but they also expect you to take full accountability and responsibility for the freedom that you've been given.

I just found it very fascinating that there is such a difference because when I went to other events like, "Yeah, this is the process, you need to do this, this and that."

Brooke Struck: To that point, I want to share an anecdote about when I also was participating in an innovation day for a client. I was giving them a bit of training on design thinking and integrating behavioural science into design and these kinds of things for them to think about as they undertake more innovation initiatives.

As we walked through the process, the outcome of the half-day workshop was like, "Well, here's a very rough MVP prototype." Then the people in the session asked me, "Oh well, what do we do with these prototypes? Who do we show them to? How do we actually test them? We need time for this. We need some resources. We need access to some clients to at least put it in front of people and get some reactions."

I said, "Well, that is an entire innovation ecosystem setup that requires policies and practices and budgets and these kinds of things." They said, "Well, I don't think we have that." I said, "My response was, it's typically the job of someone who has a title like VP of Innovation to own and curate that ecosystem."

The people looked around the room and they looked at each other and said, "We have a VP of Innovation and he doesn't do anything like that."

Angela Shurina: In every company also reminds me that it's different. You can't assume that it works the same way in every innovation department. It's life—you plan, you theorise, but very often life is nothing but something different.

Brooke Struck: I think it was Mike Tyson who said, "Everybody has a plan until you get punched in the face."

Angela Shurina: But I also learned to assume as little as possible and go into any situation with an open mind, prepared to take it either way. I feel like these days it's more needed than ever when you literally don't know which way it's going to go, and you don't want to put all of your things in one basket.

Brooke Struck: I would want to pick up on that and say, yes, I absolutely agree that we need to go in with an open mind and not knowing how things are going to play out. Also, I still believe that plan beats no plan.

Go in with a plan and the openness to say the plan is probably wrong, but the process of having built a plan and having a base case to start from is actually extremely helpful. Even if on the very first day, the first step that we take, we put our foot in a ditch and say, "Oh, actually, no, this was wrong. We need to adjust it in this way."

That is such a more helpful conversation to be able to have with people that we have some practice planning with compared to, "Well, now people are just walking in different directions and we're going to see what happens."

Angela Shurina: I guess what I also meant is now have a plan and maybe have multiple plans. I also advise always to have pre-mortem—what if the worst case happens? What are we going to do then? How can we make sure that actually the worst case maybe doesn't happen all that much? We actually put more effort into designing the ecosystem so the best case scenario has more chance to happen.

Brooke Struck: I totally agree, and this is something that I often find when I'm talking to people about scenario planning. People, when I've run scenario planning exercises and when I've talked to people about scenario planning exercises, their initial assumption is often that the purpose of the exercise is to get it right. It's to actually guess what the world is going to be like in 25 years.

Actually, that's not the purpose at all. The purpose is to illustrate a range of potential futures and to plan for those potential futures, to be able to identify what are the right moves that we—what are the moves that are smart moves to make regardless of which of these scenarios we end up in?

Also to build the muscles of having those kinds of conversations with people about where do we think this is heading based on the information that we've just seen? If it were heading in that direction, what action would we need to take? Given that we're not sure yet whether that's the direction that it's heading or whether it's 15 degrees east of there or whatever—what are the leading indicators that we should be collecting? How can we go and probe the world to create the evidence that's necessary to tell us whether we're on one trajectory or a second trajectory?

Angela Shurina: That is true. This case scenario planning and preparing the ecosystem and the resources and structures—that is powerful.

I think as we're going to the end of this podcast, a couple of questions. One question I want to definitely ask you to maybe share your take on—maybe some practical tools. With AI now here to stay and it's definitely accelerating everything and changing a lot of things, what would you say are the main differences in terms of strategic planning, maybe case scenario planning, and in terms of just approaching change management and change leadership? What's maybe what's different and what's not different?

Brooke Struck: One of the things that I would say is that this technology is being deployed very quickly. That's a way in which it's different from previous technological changes.

Somewhere there's a graph that you should share with your readers that talks about the speed of adoption of new technologies. It's specifically what is the time delay between the technology being introduced and 50% of the population having adopted it? From the time that the radio was invented to the time when half of the population had a radio was a certain number of years. The television, shorter. Telephones—well, cellular phones, shorter. Smartphones, shorter.

AI is similarly having a very short adoption curve. The time from a public release launch to 50% of the population using it is very short. That's one piece to consider—that it's happening quickly.

The second is that the most obvious applications of AI are the ones that are really only focused on efficiency, but not changing what it is that you offer or how it is that you operate. But ultimately, those ones, those applications—from a strategic perspective, it's those applications that are really the ones worth focusing on.

People tend to overestimate how much change is possible in the short term and underestimate how much change is possible in the long term. I think what I'm seeing right now is that many leaders are very excited about the efficiency gains that they can get with AI, basically with the mindset that the fundamental model of what value they deliver and how that gets created and delivered is not going to change. They're very excited about that.

I think that there's often disappointment there. There's disappointment because in fact the gains are not as large as advertised and they're not nearly as easy as advertised. The change takes more time than people expect.

On the flip side, I think that what we'll see in the longer term is that the profound structural changes that come from AI-native organisations or organisations that can be really ambitious in how deeply they're rethinking the way that their organisation functions and how they interact, how they create value for their clientele.

The ones who are really ambitious and go deep in rethinking that will see transformations that are breathtaking, that are completely upending very established verticals and industries and this kind of thing. In the public policy sphere as well—really deeply rethinking how it is that a government serves its people.

This will have profound and transformational impacts. It's not going to happen in the short term. It's going to take longer than people expect. It's going to take longer than people hope, but being ready for the world in several years to be in some ways unrecognizable from the way that it is right now.

Those are a couple of things. Anything else you wanted to ask about around AI?

Angela Shurina: Not much. To be honest, it's so much you can talk about—I think for another episode we could talk about AI. There is much information already that I believe listeners can talk about technical stuff.

I think I just want to emphasise—you started talking about strategy, and I believe having strategy is an essential part of success if organisations truly want to sort of reimagine the future. Because for me, strategy was always like who you are, what do you stand for, and how do you deliver value? Then also, think about AI as a tool that will help you to, as you mentioned, reimagine the process that you deliver that value.

It's like this upskilling problem. People like, "Well, how do we upskill people if we don't know what's going to happen?" Well, what's the value of this specific organisation and what's the value of this specific function? Not in terms of technology like "we write more emails, answer more calls"—what was the actual value? What is the problem you're solving?

I think that's where the strategic piece also becomes relevant and important. As long as you understand the North Star, what it is you're trying to do there, that's where you can reimagine. Well, maybe we don't need to write those emails and try to write 100 more of them and should do something instead.

Brooke Struck: To your question earlier, "How do we upskill people if we don't know where things are going? How can we do a reorganisation if we don't know where things are going? How can we build a strategy? How can we build culture if we don't know where things are going?"

Those are often asked as rhetorical questions, but I want to take them seriously. Actually, the clue to answering those questions is right there in the question itself. How do we upskill people if we don't know where things are going? Help them to build skills to figure out how to adapt to change.

If everything's going to be changing, then skills for change are going to be at a premium. Your organisational structure—again, organise for change. That is going to be at a premium. Your culture around learning and testing, that is going to be at a premium. Your strategy and how it is that you make bets about different ways to serve different clientele—organise your strategy around change.

These questions are often asked, again, in a rhetorical way as a way to, in a certain sense, throw up your hands and say, "Well, there's nothing we can do." But actually, no, there is something that you can do. It's to organise around change and to organise around uncertainty. Those are very powerful things.

Part 7: Closing (01:38:00 - 01:45:00)

Angela Shurina: Powerful things and skills that you can actually train people for, just like Navy SEALs you mentioned, or Marines. They do it all the time. Help people to learn how to operate in the environment of volatility and uncertainty and unpredictability. They can do it. Everyone can do it with their organisation. You're right. It's a rhetorical question, but it has the answer.

Brooke, thank you for all this information. Again, I could talk to you about that for hours and hours, and there is much to unpack in every sentence that you give in any answer and any piece of insight. Thank you.

But I invite listeners to go and explore more of your work at The Decision Lab, the Converge site. I read a few articles, but haven't explored fully what it is you offer there. Maybe can you give our listeners a list of why would they want to explore your work, what kind of services they can get, and where they should go to explore and connect with you?

Brooke Struck: Sure. The company that I launched 3 years ago is called Converge. People can find us at convergehere.com. The services that I'm offering are transformation facilitation services—helping organizations with strategic transformations and cultural transformations.

The kinds of clients that I'm working with are leaders who recognise that change really needs to begin with them. We've talked quite a bit throughout our conversation about the importance of personal growth in this journey. It's recognising that if I want different outcomes, I need to change the system. As a leader, one of the biggest determinants of why the system operates the way that it does and why the system is set up the way that it is, is because of my decisions and my behaviour and the behaviour of my leadership team around me.

The way that I'm helping organisations is through accompanying their leadership groups through the process of designing new strategies, through the process of overhauling their culture or renovating their culture, to borrow a phrase from Kevin Oakes.

That's the kind of work that I'm doing. I've also recently launched a keynote and workshop offering. Something that I've seen in the last few months is that with all of the socio-political, socio-economic changes that we're seeing, organisations have really struggled to commit to bigger transformations. I think that there's some wisdom in there, to the point that we've been discussing—how do I figure out where to go if things seem to be changing much? We need to do strategy a bit faster.

In response to that, I've put together a keynote and workshop offering which is really oriented towards organisations that are just starting to consider change and starting to think through: are we ready for change? What kind of change are we thinking about? What is the urgency?

I asked these two questions—what is it about the status quo that wouldn't be acceptable to continue for the next 18 or 24 months? That's exactly what this new smaller offering is about. It's helping organisations just to start scratching that surface of what is the change that we might be ready for and how can we set the table for this deeper transformation before we dive in, because people are skittish about diving in with both feet.

Angela Shurina: Amazing. So it's all on your website, right? Convergehere.com.

Brooke Struck: Yep. All of the information about the offerings is there. We also have our media page there, so that's where you can find all the thought leadership work. This podcast will eventually be featured there as well.

Really, I appreciate this conversation. I appreciate you inviting me, and I hope that listeners get a lot out of it.

Angela Shurina: Thank you, Brooke. We'll link this in the show notes and also a little bit more information about you. I invite our listeners to check it out, connect with you, learn from you, and also stay tuned for future episodes of Change Wired Podcast. Thank you, Brooke, for being such an amazing guest on the show.

Brooke Struck: Thanks for having me.

Leave A Comment