This piece was co-authored with Mike James Ross, who is the co-author of “Intention: The Surprising Psychology of High Performers”, former CHRO at La Maison Simons and current board member and executive advisor.

This piece is also part of the Essential Readings for the keynote offering, "Committed to the Team, Committed to the Mission"

A promise of light in the dark…

The year 2024 set a record for CEO turnover, according to leadership advisory firm Russell Reynolds Associates, and 2025 looks like it’ll be even worse.

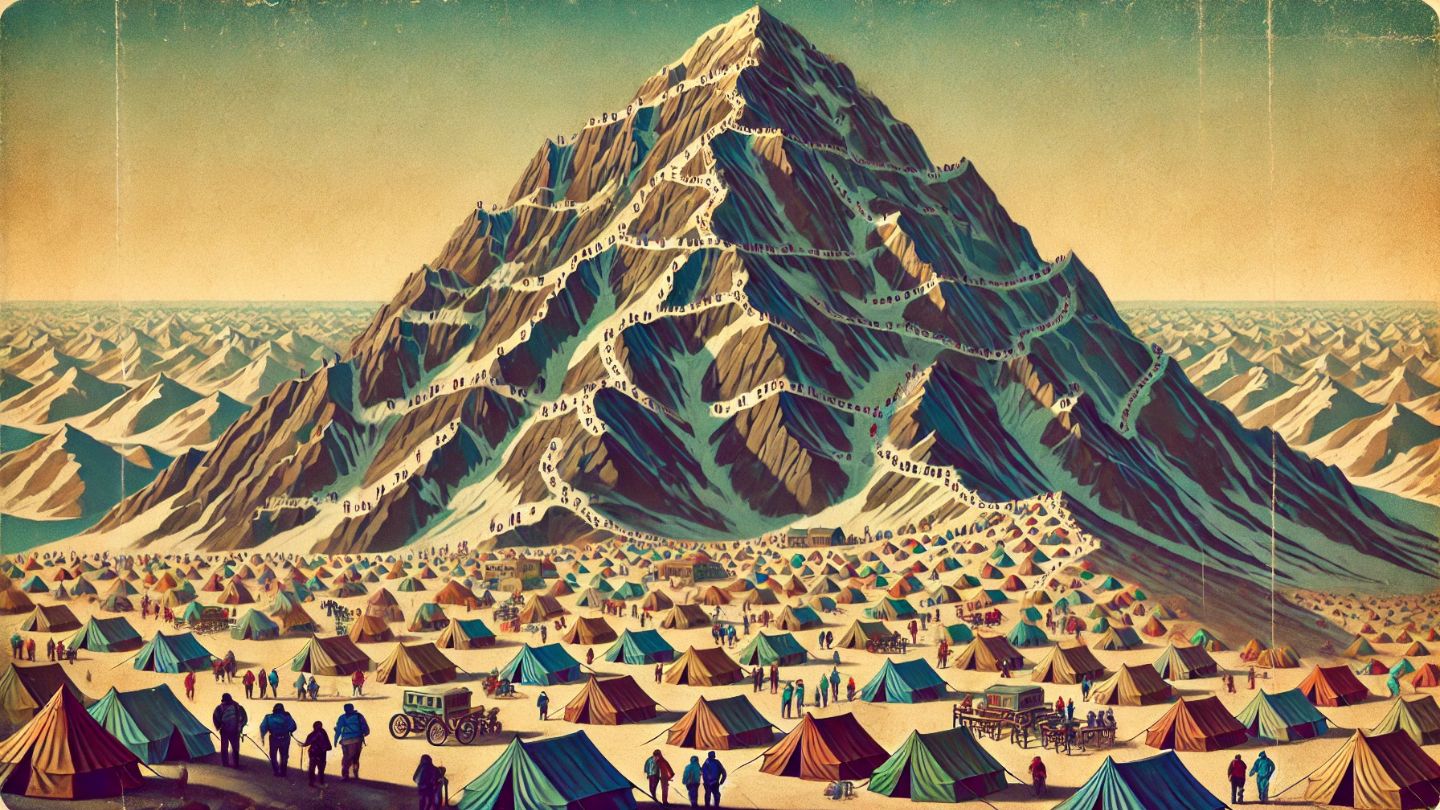

Often, a replacement executive is brought in as organizations move through natural phases. To draw an analogy to mountain climbing, reaching base camp and reaching the summit are two different phases, each with a separate skillset and each necessary to reach the ultimate goal.

However, when there’s a leadership change, it is all too easy for the incoming executive to lean into a convenient narrative: “The old way of doing things doesn’t cut it and that’s why we need to change.”

The logic of this is as attractive as it is simple – and dangerous. The urgency to adopt the new is driven by the inadequacy of the old. An executive stepping into a new role might initially have the intention to “spend the first 45 days listening,” but once they arrive on the job and begin feeling the pressure to quickly demonstrate value, the idea of “out with the old and in with the new” can be appealing as a lever to drive better results now.

… which turns out to be a trap

In vilifying the past, you run two important risks:

First, while some part of how we’ve operated surely needs to change, this narrative completely ignores that many other parts actually work well. Consider a 185-year-old company like La Maison Simons. Companies simply don’t thrive and flourish for two centuries (or even two decades) without getting a lot of things right. By vilifying the past wholesale, we’re casting shade too widely.

Second, in criticizing processes it’s perilously easy to disparage people as well. Our intention as leaders is to motivate our teams to change, but we can easily demotivate them if our words sound to them like, “You were incompetent and doing it all wrong.”

The longer way ‘round is the shorter way home.

While not as simple, a more effective storyline around change is one that demonstrates the continuity of past, present and future. This is especially true in older organizations with rich histories.

By celebrating what came before and recognizing that it was necessary to get us where we are now, we can focus our attention with enthusiasm and excitement on the potential of what is to come.

There are three elements that we’ve seen work in practice.

- Bring together a dynamic mix of participants: When crafting your narrative, bring a group of people together who have a deep grasp of the organization’s past, the current state of operations and the vision for the future. The balance of your narrative will reflect how past, present and future are represented in your group (considering the number of people as well as how loud or quiet their voices are).

- Use a process that engages hearts as well as minds: An effective narrative must fit with the new strategic direction that’s being advocated and, if done well, will help to ensure alignment and engagement with the plan. At the same time, most corporate cultures are too logic-driven. Storytelling is ultimately an activity that needs to connect at the level of human emotions. This work is equal parts conceptual and interpersonal, strategic and cultural. Draw out those evocative stories, focusing on what has gone well and how that can help us to achieve our new goals.

- Always keep the messenger in mind: A story about the organization’s deep past seems more genuine coming from someone who’s been there a long time. An inspirational story about the future will land strongly coming from someone who’s known for being skeptical about change. And remember that a critical word about the past can sound like “We need to change,” from an old hand whereas it can sound like “You need to change,” coming from a new leader.

Finally, here are three questions we’ve found helpful to keep leaders aligned during this process.

- As we craft this story together, am I approaching this with curiosity and openness to learning or a fixed mindset just looking to confirm what I’ve already decided?

- When we’re diving into stories of successes and failures, did we reach these outcomes because of what we were doing or in spite of it? The best option sometimes turns out badly and a broken clock can be right twice a day.

- What is the price of getting this “right” on the organization? Be careful of short-term victories that exact a long-term cultural cost. Remember, that culture is a crucial component to strategy and is ignored at your peril.

By combining these approaches and mindsets, we’ve seen stronger commitment to change, better continuity and greater opportunities for leadership to shine across many organizations. Given that we’re all living in a world that requires constant change, being anchored in what worked well can make all the difference.

Leave A Comment